|

Click here to return to the main site. Book Review

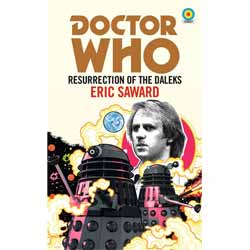

The TARDIS is ensnared in a time corridor, catapulting it into derelict docklands on 20th-century Earth. The Doctor and his companions, Tegan and Turlough, stumble on a warehouse harbouring fugitives from the future at the far end of the corridor – and are soon under attack from a Dalek assault force. The Doctor’s oldest enemies have set in motion an intricate and sinister plot to resurrect their race from the ashes of an interstellar war. For the Daleks’ plans to succeed, they must set free their creator, Davros, from a galactic prison – and force the Doctor to help them achieve total control over time and space. But the embittered Davros has ideas of his own… It’s taken a while (37 years, in fact), but at last there’s a Target novelisation of Resurrection of the Daleks! Back in the 1980s, the original Target Books imprint was unable to reach an agreement with writer / script editor Eric Saward and Dalek originator Terry Nation to allow Saward (or any other writer) to adapt his scripts for the 1984 Fifth Doctor serial. Virgin Books, the imprint that succeeded Target, tried again in the early 1990s, Saward started work and the novelisation was actually announced, but again the project stalled. Now the paperback edition of the completed 2019 book is being published in the resurrected Target imprint… but was it worth the wait? This novelisation is not what I had been expecting. It’s not the number of differences between the book and the original serial that causes me to raise my eyebrows. After all, other long-delayed Doctor Who adaptations that have been completed in recent years, based on scripts by Douglas Adams, have contained large amounts of new material, reinstated from earlier versions of scripts and storylines. No, it’s the nature of the changes that surprises me. Whereas the screen version of Resurrection was almost unremittingly grim, the novelisation often adopts a comical tone. Perhaps I should have expected this. Saward’s 1986 novelisations of The Twin Dilemma and Slipback contain several Adams-style digressions into light-hearted background information. So does this book, which holds forth on such subjects as how the prison station got its name (the Vipod Mor, a designation accidentally reused from Slipback) and an unlikely mix-up between a producer of preserves and a manufacturer of missiles. On other occasions, the novelist deliberately undermines the drama of a situation he has created by taking a turn for the bathetic. For instance, after significantly raising the stakes during the initial TARDIS scene, placing the ship and its crew in danger of destruction (rather than being merely off course and out of control, as they were on screen), Saward punctures the tension with the understatement, “The greatest Time Lord of them all was having a really bad day.” Exciting lines that the writer had scripted for Davros are sabotaged by having Commander Gustav Lytton ponder that the villain talks too much and by describing the Dalek creator as squawking “like Florence Foster Jenkins aiming for a high C”. The Daleks themselves come in for similar stick. Lytton finds the species as a whole to be “noisy, aggressive and highly repetitive,” and regards the Supreme Dalek as downright odd. The latter’s dialogue is often “oozed” or “purred”, he makes noises similar to burps and grunts – and he even attempts a joke! Terry Nation would not have approved. (Some readers may also be sceptical about Daleks muttering or contemplating insubordination, but there are precedents for both of these in the television show.) I dare say that much of this satire arises from Saward’s feelings about writing for the Daleks and his dissatisfaction with his own scripts. Both the writer and the critics have pointed out the convoluted nature of the serial’s plot, in which too many ideas jostle for attention and not all of them are developed as fully as they might have been. However, I don’t think taking the mickey out of the source material is the solution. It’s an approach that was successful with The Twin Dilemma and Slipback, because the broadcast versions already contained a lot of humour, but a story like this (in common with the similarly convoluted Evil of the Daleks, to which Resurrection owes much of its inspiration) needs to be told straight. Poke fun at it, and the whole thing could fall apart. Fortunately, Saward takes other aspects more seriously. He explores the inner thoughts of his characters, which is particularly effective in the case of the ruthless Lytton, the conflicted Sergeant Raymond Arthur Stien and the ill-fated homeless smoker at the beginning of the adventure, who is given the name Mr Jones. The writer clearly enjoys describing the rain-soaked streets of Shad Thames, where the warehouse entrance to the Daleks’ time corridor is located. He makes the most of all the grisly deaths that take place in this tale, by not only describing them when they occur but also foretelling many of them beforehand, with phrases like, “Little did they know it would be the last time they would hear him speak those words.” We are made aware of the Daleks’ involvement at an earlier point than in the television serial, via Lytton’s musings and the Doctor’s deductive reasoning. The Time Lord concludes that the time corridor must be the work of the demented pepper pots while the TARDIS is still ensnared in the temporal phenomenon. However, once the time travellers arrive in 1984 London, this realisation is all but forgotten, and the Doctor’s exploration of the warehouse reverts to the less urgent investigation that it was on screen. The novelist resolves some but not all of his original story’s implausibilities, including the inconsistent nature of the Daleks’ human duplicates and Davros’s awareness that the Doctor is a Time Lord. The time corridor is given a computerised intelligence, allowing it to defend itself, and its London entrance is effectively disguised in a manner similar to the TARDIS’s chameleon circuit. However, when it comes to explaining the science behind such marvels, it would have been better if he hadn’t tried. We are informed that the operation of the Doctor’s craft involves “time bubbles” suspended in “stabilising dampers.” When these bubbles burst, the TARDIS risks becoming trapped “in a crack in time, causing the Doctor, and his two friends, to relive the same single moment over and over again.” Being caught in such a temporal loop is, nonsensically, a greater threat to the Time Lord, whose regenerative powers would condemn him to “a permanent state of living hell.” The source of the time corridor, we are told, is a beam of light projected from the Dalek ship. This cuts through space until, at a prearranged point, gravity (somehow) affects it, forcing the light “to spiral and twist its way through the cracks and fissures in the time-space continuum”, until pressure transmogrifies it “into the swirling mass of a time corridor.” Saward himself seems to realise that this kind of description is not where his strengths lie, and so later claims that to comprehend how the time corridor works “would require a double-first in mathematics plus the help of a dozen Albert Einsteins and several Stephen Hawkings on the side just to interpret the first five lines of the principle.” The author also throws in references to other Doctor Who adventures that he wrote or edited. Humans are referred to as Tellurians, as they are in several Robert Holmes scripts. They enjoy drinking Voxnic, a potent alcoholic beverage previously knocked back in Slipback and the novelisation of The Twin Dilemma. Speelsnapes (Revelation of the Daleks, The Trial of a Time Lord) are mentioned and time spillage (The Mark of the Rani, Slipback) occurs. Most frequent, however, are the allusions to the Terileptils, reptilian beings introduced in The Visitation, and tinclavic, a malleable metal that they are said to mine. I know Saward created them, but there are other species and substances in the Whoniverse! Here tinclavic is used in the construction of devices operated by Time Lords, Daleks and Tellurians alike, despite the fact that, according to the Doctor in The Awakening, the Terileptils mine the stuff for the more or less exclusive use of the inhabitants of the planet Hakol. (That’s in the star system Rifter, you know.) As a result of all the additions, we are two-fifths of the way through the book before we reach the end of the material from Part One of the four-part serial. Then, as with his approach to scientific explanations, the novelist seems to change his mind mid-narrative. From this point on, he is more economical with his embellishments to the original plot – apart from a lengthy tour of the TARDIS interior and a bemusing coda. Moreover, several key developments, such as the fate of Colonel Archer, and the arrival and ‘recruitment’ of Davros’s helper Kiston, are conveyed only in summary. Did Saward get bored? Was he struggling to meet the deadline? Given the duration of recent Adams and movie adaptations published by BBC Books, I doubt he was in danger of breaching the upper word limit. The complete text is presented in this 192-page paperback edition, though the type size is very small. For me, the novelisation of Resurrection of the Daleks is far from successful. Sure, it has its good points, but for every instance of admirable prose, there’s a passage that has me wondering, “What was Saward thinking?” The author’s sardonic tone works better in his next book, based on the blackly comical Revelation of the Daleks, whose paperback edition joins the Target library at the same time as this one. 5 Richard McGinlay Buy this item online

|

|---|