Just like the best of written science fiction, Galactica is open to many interpretations, its combination of the purely visual and metaphysical and its exploration of cosmology and ontology made for a rich brew which attempted to explore the religious and philosophical monoliths which at the same time unite and divide us as a race. A contextual or deterministic examination of the show would fill a book. However, over the course of three articles, Charles Packer hopes to give a glimpse of where Galactica came from, its reflection on what it is to be human and the technical tricks it used along the way...

In the first article we looked at how both the original and re-imagined versions of Galactica were children of their time and cultural influences, the original was hopeful, with a strong leaning towards a specific religious theme - Mormonism. The new Galactica would take a more balanced view of both religion and politics. A deconstructionist look at the show will help tease out some of the themes and motifs which were used.

In the first article we looked at how both the original and re-imagined versions of Galactica were children of their time and cultural influences, the original was hopeful, with a strong leaning towards a specific religious theme - Mormonism. The new Galactica would take a more balanced view of both religion and politics. A deconstructionist look at the show will help tease out some of the themes and motifs which were used.

But firstly Moore needed to ease the apprehensions of older fans before he could take them on a new spiritual journey. To this end, many individual iconic elements were lifted from the old series, given a dust off and presented with a new slant.

It was not just the tonal changes to the script that set the new version apart; the way it was created and presented set it apart from not only its predecessor but also made the move away from much of what passed as science fiction on television, with its reliance on technobabble and effects to shore up, what was often, weak story telling. Galactica challenged its audience to question.

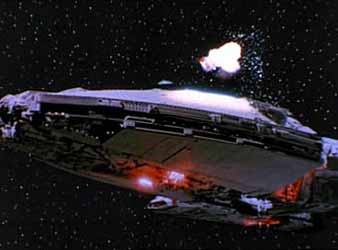

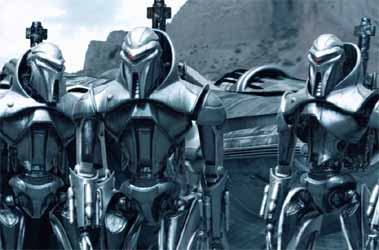

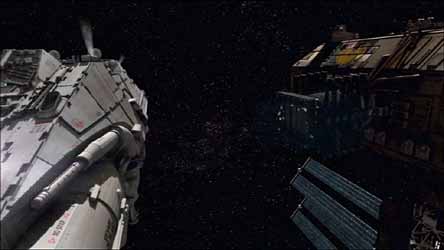

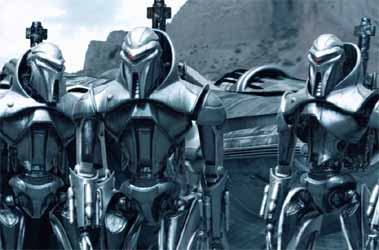

The new miniseries opens after a forty year truce has been in place. Visually there is little at this stage to differentiate the new series, either in content or stylistically, as the credits open to a shot of a familiar Colonial Shuttle, substantially the type which appeared in the original show. The diplomat which arrives carries documents which clearly show the original Cylon Model, once more tying it to the original. Things change, but not radically when the two mechanical Cylons enter and take position on either side of the door. Although their overall design has been updated, the red scanning eye betrays their origins. Then Caprica, a tall beautiful woman in a blood red outfit enters, walks up to the diplomat and asks: “Are you alive?” before planting a passionate Judas kiss on his lips. The camera pulls back to reveal a substantially redesigned Baseship. Form this moment on the stylistic changes come thick and fast when we join the story proper aboard the Galactica. Gone are the blandly bright interiors, to be replaced with a ship which has a much more used military feel. With the ship being turned into a museum, it gives Moore another chance to tie the two shows together via the exhibits.

The new miniseries opens after a forty year truce has been in place. Visually there is little at this stage to differentiate the new series, either in content or stylistically, as the credits open to a shot of a familiar Colonial Shuttle, substantially the type which appeared in the original show. The diplomat which arrives carries documents which clearly show the original Cylon Model, once more tying it to the original. Things change, but not radically when the two mechanical Cylons enter and take position on either side of the door. Although their overall design has been updated, the red scanning eye betrays their origins. Then Caprica, a tall beautiful woman in a blood red outfit enters, walks up to the diplomat and asks: “Are you alive?” before planting a passionate Judas kiss on his lips. The camera pulls back to reveal a substantially redesigned Baseship. Form this moment on the stylistic changes come thick and fast when we join the story proper aboard the Galactica. Gone are the blandly bright interiors, to be replaced with a ship which has a much more used military feel. With the ship being turned into a museum, it gives Moore another chance to tie the two shows together via the exhibits.

Here Moore chooses, amongst the familiar or at least vaguely familiar, to introduce one of his most contentious changes, as we follow Starbuck jogging through the interior of the ship. This is not a recognisable Starbuck, as this one is Kara Thrace a woman, played by Katee Sackhoff, who smokes, drinks and fights. Even as a passing fan of the original show I never really understood why this point should have been contentious, nobody complained when Sigourney Weaver played Ripley in Alien (1979), a role that was written for a man. One possible explanation is that as a female character she isn’t, unlike Caprica 6, overtly sexualised. Even in these enlightened times it would seem that we still prefer strong female characters to over emphasis their gender - Angelina Jolie, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), Milla Jovovich, Resident Evil (2002), Ultraviolet (2006) and Kate Beckinsale, Underworld (2003) - certainly within the science fiction genre Buffy and her ilk seems to have hardly made a dent, leaving women mainly with roles within which they either need rescuing, or if they are to be presented as empowered, then they are empowered in either skimpy or tight fitting clothing. Katee Sackoff’s Starbuck successfully challenged this stereotype and her strong performance in the role silenced much of the criticism.

Here Moore chooses, amongst the familiar or at least vaguely familiar, to introduce one of his most contentious changes, as we follow Starbuck jogging through the interior of the ship. This is not a recognisable Starbuck, as this one is Kara Thrace a woman, played by Katee Sackhoff, who smokes, drinks and fights. Even as a passing fan of the original show I never really understood why this point should have been contentious, nobody complained when Sigourney Weaver played Ripley in Alien (1979), a role that was written for a man. One possible explanation is that as a female character she isn’t, unlike Caprica 6, overtly sexualised. Even in these enlightened times it would seem that we still prefer strong female characters to over emphasis their gender - Angelina Jolie, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), Milla Jovovich, Resident Evil (2002), Ultraviolet (2006) and Kate Beckinsale, Underworld (2003) - certainly within the science fiction genre Buffy and her ilk seems to have hardly made a dent, leaving women mainly with roles within which they either need rescuing, or if they are to be presented as empowered, then they are empowered in either skimpy or tight fitting clothing. Katee Sackoff’s Starbuck successfully challenged this stereotype and her strong performance in the role silenced much of the criticism.

This juxtaposition of the known with the new would be a motif that would reoccur through the whole four seasons - sometimes for continuity, sometime to help the original fans to feel that they might still be in Kansas and sometimes just from a sense of playfulness, witness the Serenity from Firefly (2002) as it comes in for a landing in Caprica city, just before we meet Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell), the show's other strong female lead, for the first time. To further keep older fans in their comfort zone, many of the designs for the ‘78 fleet are recreated in the new show, including, amongst others, The Celesta, The prison ship The Astra Queen, the Colonial Movers and the infamous Majahual, which was originally made from three discarded film cans. Some of the musical themes which had originated in the original show were likewise peppered, for flavouring, amongst the new soundtrack. Some of the props, like the Galactica and the Vipers, were updated, with the biggest makeover reserved for the Cylon craft, all of which had a radical design overhaul. As the show progressed fans were delighted when pure homage ended and the show fully embraced its heritage with the old Cylon Centurian, Baseship and Raider finally making it onto the screen.

This juxtaposition of the known with the new would be a motif that would reoccur through the whole four seasons - sometimes for continuity, sometime to help the original fans to feel that they might still be in Kansas and sometimes just from a sense of playfulness, witness the Serenity from Firefly (2002) as it comes in for a landing in Caprica city, just before we meet Laura Roslin (Mary McDonnell), the show's other strong female lead, for the first time. To further keep older fans in their comfort zone, many of the designs for the ‘78 fleet are recreated in the new show, including, amongst others, The Celesta, The prison ship The Astra Queen, the Colonial Movers and the infamous Majahual, which was originally made from three discarded film cans. Some of the musical themes which had originated in the original show were likewise peppered, for flavouring, amongst the new soundtrack. Some of the props, like the Galactica and the Vipers, were updated, with the biggest makeover reserved for the Cylon craft, all of which had a radical design overhaul. As the show progressed fans were delighted when pure homage ended and the show fully embraced its heritage with the old Cylon Centurian, Baseship and Raider finally making it onto the screen.

This need to stamp Moore’s vision on the Galactica universe extended to changing the personality traits of more than one of the cast members. Gone was Lorne Green’s kindly patriarch Adama, to be replaced with Edward James Olmos’s grizzled warrior who had fought in the initial Cylon War. His commitment to his career had cost him a lost marriage, a dead son and the loss of his relationship with his only surviving son. Likewise, Boomer (Grace Park) turned into a woman and Apollo swapped his name for Lee (Jamie Bamber).

This need to stamp Moore’s vision on the Galactica universe extended to changing the personality traits of more than one of the cast members. Gone was Lorne Green’s kindly patriarch Adama, to be replaced with Edward James Olmos’s grizzled warrior who had fought in the initial Cylon War. His commitment to his career had cost him a lost marriage, a dead son and the loss of his relationship with his only surviving son. Likewise, Boomer (Grace Park) turned into a woman and Apollo swapped his name for Lee (Jamie Bamber).

This Adama vocalised many of the central themes Moore explored in the series, themes which were set out in Adama’s decommissioning speech, so much so that it is worth reminding ourselves of the most salient points - his emphasis on the flawed fragility of humans as a species, on their refusal to take responsibility for their own flawed creations, the Cylons, and he poses the question, why are we worth saving from the inevitable day of reckoning?

But it was a day of reckoning that Moore provided. Examined again, we can see that many of the themes which would be played out across Galactica’s four seasons are already contained in Adama’s speech: themes of religion and philosophy, of existential responsibility and the flawed nature of man. This idea of a flawed creation would see the characters engage in many actions which would be unthinkable on many other shows. President Roslin orders the death of Leoben (Callum Keith Rennie) without considering that she is killing another sentient creature, an act which would otherwise be against her own belief system. This notion of free will, which may initially seem a comfort unfortunately also, involves moral responsibility and the possibility of redemption. It is this which Adama tries to address in his speech - “The day comes when you can't hide from what you've done anymore”. At some time or another all the major characters have to face this moment of truth. Starbuck is the first, quite early on in the story, when she has to admit to Adama that she passed his son, on his flight test, even though he should have failed, an act which contributed to his death. Baltar is put on trial for his actions on New Caprica, Gaeta and Zarek pay the ultimate sacrifice for their betrayal. The most unnerving instance of this is when Saul Tigh literally has to look into the eyes of his wife, whom he had murdered.

But it was a day of reckoning that Moore provided. Examined again, we can see that many of the themes which would be played out across Galactica’s four seasons are already contained in Adama’s speech: themes of religion and philosophy, of existential responsibility and the flawed nature of man. This idea of a flawed creation would see the characters engage in many actions which would be unthinkable on many other shows. President Roslin orders the death of Leoben (Callum Keith Rennie) without considering that she is killing another sentient creature, an act which would otherwise be against her own belief system. This notion of free will, which may initially seem a comfort unfortunately also, involves moral responsibility and the possibility of redemption. It is this which Adama tries to address in his speech - “The day comes when you can't hide from what you've done anymore”. At some time or another all the major characters have to face this moment of truth. Starbuck is the first, quite early on in the story, when she has to admit to Adama that she passed his son, on his flight test, even though he should have failed, an act which contributed to his death. Baltar is put on trial for his actions on New Caprica, Gaeta and Zarek pay the ultimate sacrifice for their betrayal. The most unnerving instance of this is when Saul Tigh literally has to look into the eyes of his wife, whom he had murdered.

Adama, who with Roslin, functions in a latter day Moses role, leading their people to the Promised Land, also poses the ultimate question: Why are we here? “Why are we as a people worth saving?” For some in the show the answer was as obvious as it was trite, that their unquestioning belief in a god or gods were enough justification for their existence. And, for the Cylons especially, it was enough for them to unquestionably eradicate the majority of humanity, in the furtherance of their enigmatic plan which was never explained or explored in the four seasons of the show - though it is possibly alluded to in the new show Caprica. Hopefully, when later in the year the Edward James Olmos helmed ‘The Plan’ sees the light of day, some of the questions will be answered.

Adama, who with Roslin, functions in a latter day Moses role, leading their people to the Promised Land, also poses the ultimate question: Why are we here? “Why are we as a people worth saving?” For some in the show the answer was as obvious as it was trite, that their unquestioning belief in a god or gods were enough justification for their existence. And, for the Cylons especially, it was enough for them to unquestionably eradicate the majority of humanity, in the furtherance of their enigmatic plan which was never explained or explored in the four seasons of the show - though it is possibly alluded to in the new show Caprica. Hopefully, when later in the year the Edward James Olmos helmed ‘The Plan’ sees the light of day, some of the questions will be answered.

This leaning to the acceptance of a religious reading of Galactica is no whim of the imagination, either. As a wry joke, or a nod towards their influences, the show produced a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1492 -1498), with the disciples replaced by characters from the show. When it first hit the net there was an enormous amount of speculation as to its meaning, especially as Caprica 6 stands in for Jesus, in her signature red dress, possibly a reference to blood and sacrifice, though my personal feeling is that this represented a sort of joke on the program maker’s part. For a start there are not enough figures in the picture to represent the twelve apostles and a straight one to one mapping of the characters in the painting and those out of Galactica creates more confusion than illumination.

Magic, religion and science are not mutually exclusive areas of interest. Most science fiction stories which examine the nature of God and its interaction with its creation tend towards the rational, unlike Galactica which was happy to fuse the scientific with the mystical. These elements interact in science fiction in much the same way as they do in real life - as a means for humanity to make some sense and meaning in the cosmic conundrum with which it faced, the answers to which are likely to be found in a blending of the three.

Not all of the characters demonstrate an initial belief system and it is not without its irony that the unseen hand which moves the event should choose Baltar, one of the most self centred, weak and hedonistic people, to effectively become an instrument of God. Or is it? If God created the universe, then he also created lions, snakes and scorpions, both the hunter and the prey are equal in the eyes of the Galactica God, it is only humanities folly to consider themselves the ennobled chosen of God, even though Adama reminds them that "...we'll still let people go to bed hungry because it costs too much to feed the poor... we still commit murder for greed or spite or jealousy... and we visit all of our sins upon our children." Even with self enlightened view of the humans of the twelve colonies as being flawed creations, this did not stop them playing God and creating new life.

Fears about the consequences of creating life in mans image or otherwise has been a rich part of our fiction. The earliest serials like Homunculus (1915) where a scientist creates life which is evil, that is finally destroyed with a bolt of lightning, possibly from God. Metropolis (1927) went a step further with the robotic Maria who becomes indistinguishable to the original, except for her heightened sexuality, a little like Caprica 6. Once more mankind is nearly brought to its knees by its own creation and of course poor Victor Frankenstein is destroyed by his own creation. The book’s subtitle “The Modern Prometheus” acted as a warning to mankind that there are some things which should not be attempted, the creation of life is one of them. The sentient races in Galactica have yet to learn the lesson of Prometheus who was condemned to repeat the same torture over and over again for stealing fire - the essence of life - from the gods. The punishment holds not just for biological human life but also for artificial life. Like the computer in Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970) and the Robots in Westworld (1973) we create sentience at our own peril. As Adama puts it: “We decided to play god. Create life. And when that life turned against us, we comforted ourselves in the knowledge that it wasn't really our fault, not really. It was the Cylons that were flawed. But the truth is... we're the flawed creation.”

Fears about the consequences of creating life in mans image or otherwise has been a rich part of our fiction. The earliest serials like Homunculus (1915) where a scientist creates life which is evil, that is finally destroyed with a bolt of lightning, possibly from God. Metropolis (1927) went a step further with the robotic Maria who becomes indistinguishable to the original, except for her heightened sexuality, a little like Caprica 6. Once more mankind is nearly brought to its knees by its own creation and of course poor Victor Frankenstein is destroyed by his own creation. The book’s subtitle “The Modern Prometheus” acted as a warning to mankind that there are some things which should not be attempted, the creation of life is one of them. The sentient races in Galactica have yet to learn the lesson of Prometheus who was condemned to repeat the same torture over and over again for stealing fire - the essence of life - from the gods. The punishment holds not just for biological human life but also for artificial life. Like the computer in Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970) and the Robots in Westworld (1973) we create sentience at our own peril. As Adama puts it: “We decided to play god. Create life. And when that life turned against us, we comforted ourselves in the knowledge that it wasn't really our fault, not really. It was the Cylons that were flawed. But the truth is... we're the flawed creation.”

Where Galactica diverges from many of the shows, when it includes religious elements, which preceded it is in its equal acceptance of the validity of both the monotheistic faith of the Cylons and the polytheistic pantheon of gods that the colonists worship. This is not the first time this has happened, even the Imaginary ‘Force’ is treated reverentially in Star Wars (1977). This allocation of faith systems sets up an uncomfortable resonance in the audience. Many, if not most, will adhere to the monotheistic view of a single god, but Galactica ascribes these religious attributes to what is initially viewed as the bad guys. So, if we are cheering on the race that more closely adheres to a lot of peoples religious sensibilities, are we making a pact with the devil? Galactica makes no such distinction. The belief in a pantheon of gods, based loosely on Greek mythology, is given both equal time and importance. it's use is reminiscent of many human conflicts where both parties believe that God is on their side.

Where Galactica diverges from many of the shows, when it includes religious elements, which preceded it is in its equal acceptance of the validity of both the monotheistic faith of the Cylons and the polytheistic pantheon of gods that the colonists worship. This is not the first time this has happened, even the Imaginary ‘Force’ is treated reverentially in Star Wars (1977). This allocation of faith systems sets up an uncomfortable resonance in the audience. Many, if not most, will adhere to the monotheistic view of a single god, but Galactica ascribes these religious attributes to what is initially viewed as the bad guys. So, if we are cheering on the race that more closely adheres to a lot of peoples religious sensibilities, are we making a pact with the devil? Galactica makes no such distinction. The belief in a pantheon of gods, based loosely on Greek mythology, is given both equal time and importance. it's use is reminiscent of many human conflicts where both parties believe that God is on their side.

This is a deliberate theological point which the show makes. Towards the close of the last season we, as an audience, are informed, by head Baltar and head 6, that not only does God exist, but that firstly he doesn’t really like being referred to as such and, secondly, he is certainly not on anybody’s side. This opens up the possibility that both the humans and Cylons could be equally right or wrong in their notion of God. If this were the case how, as an audience, are we to make sense of the numerous visions which pepper the show, including the portentous visions of the future which are given to Baltar, Roslin, Caprica 6 and Kara? It would seem that the visions of the opera house do come true, as do Kara’s paintings of the damaged Baseship. The show even implies that Kara has been groomed, so to speak, from an early age, so that she is in the correct position to jump the Galactica to safety. The lack of answers and the multilayered manner in which religion is introduced often leaves many questions unanswered. Roles appear interchangeable over the course of the show with more than one character taking on the messianic role.

This is a deliberate theological point which the show makes. Towards the close of the last season we, as an audience, are informed, by head Baltar and head 6, that not only does God exist, but that firstly he doesn’t really like being referred to as such and, secondly, he is certainly not on anybody’s side. This opens up the possibility that both the humans and Cylons could be equally right or wrong in their notion of God. If this were the case how, as an audience, are we to make sense of the numerous visions which pepper the show, including the portentous visions of the future which are given to Baltar, Roslin, Caprica 6 and Kara? It would seem that the visions of the opera house do come true, as do Kara’s paintings of the damaged Baseship. The show even implies that Kara has been groomed, so to speak, from an early age, so that she is in the correct position to jump the Galactica to safety. The lack of answers and the multilayered manner in which religion is introduced often leaves many questions unanswered. Roles appear interchangeable over the course of the show with more than one character taking on the messianic role.

Messianic characters are not unknown in science fiction, both written and filmed. Valentine Michael Smith, (Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein pub. 1961) - Klattu (The Day the Earth Stood Still, 1951) Frank Herbert’s Paul Atreides (Dune pub 1965, filmed 1984, TV series 2000). What made Baltar transform from sceptic to true believer was never designed so that the audience believed it. It played on the audiences own preconceptions of what a character which fulfilled this role should be. Baltar lacked either the humility or personal enlightenment usually required in a messiah. As a rationalist Baltar is only interested in God insofar as he can use other peoples beliefs to further his own agenda, making his conversion the strongest in the show and the most unlikely. The show does not deal with right and wrong in a trite manner either and, In fact, a lot of the characters which have the strongest faiths do not survive to the end of the show. Ultimately, although Baltar has a pivotal role in bringing about a new equilibrium, the messianic role is fulfilled by Kara Thrace, who dies and is reborn in an act of sacrifice which will ultimately lead to mankind’s salvation.

Messianic characters are not unknown in science fiction, both written and filmed. Valentine Michael Smith, (Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein pub. 1961) - Klattu (The Day the Earth Stood Still, 1951) Frank Herbert’s Paul Atreides (Dune pub 1965, filmed 1984, TV series 2000). What made Baltar transform from sceptic to true believer was never designed so that the audience believed it. It played on the audiences own preconceptions of what a character which fulfilled this role should be. Baltar lacked either the humility or personal enlightenment usually required in a messiah. As a rationalist Baltar is only interested in God insofar as he can use other peoples beliefs to further his own agenda, making his conversion the strongest in the show and the most unlikely. The show does not deal with right and wrong in a trite manner either and, In fact, a lot of the characters which have the strongest faiths do not survive to the end of the show. Ultimately, although Baltar has a pivotal role in bringing about a new equilibrium, the messianic role is fulfilled by Kara Thrace, who dies and is reborn in an act of sacrifice which will ultimately lead to mankind’s salvation.

Galactica’s vision of God also nicely bypasses the deterministic problem of free will Vs an omnipotent creator. This God leads and nudges his creations to get a desired outcome - “All this has happened before, all of this will happen again” - an omnipotent God would not need to go through so many iterations of creation, therefore his creations really do have free will. This is actually a simplistic view of the concept of God in Galactica. If God was tinkering, trying to get it right, how do we then explain Roslin’s visions which ultimately come true? Or that Leoben is able with some accuracy to predict Kara’s finding of Kobol and Earth? If the characters had true free will none of this would be known.

Galactica’s vision of God also nicely bypasses the deterministic problem of free will Vs an omnipotent creator. This God leads and nudges his creations to get a desired outcome - “All this has happened before, all of this will happen again” - an omnipotent God would not need to go through so many iterations of creation, therefore his creations really do have free will. This is actually a simplistic view of the concept of God in Galactica. If God was tinkering, trying to get it right, how do we then explain Roslin’s visions which ultimately come true? Or that Leoben is able with some accuracy to predict Kara’s finding of Kobol and Earth? If the characters had true free will none of this would be known.

The Cylons attitude towards the final five, which is tantamount to worship and therefore not in line with a one God theory, is easier to explain for those who have watched the whole show. Most of our supposed understanding of the Cylons monotheism comes from Head Caprica 6 when she is talking to Baltar, a creature which we later discover is not really Cylon. So how much do we really end up knowing about their religious beliefs?

In the end Galactica offered up a veritable feast of the known and the unknown. It is down to personal taste as to whether they were successful in their endeavour, though the rich tapestry of religion, politics and survivalist morality nearly always provided food for thought.

Return to...

In the

In the  The new miniseries opens after a forty year truce has been in place. Visually there is little at this stage to differentiate the new series, either in content or stylistically, as the credits open to a shot of a familiar Colonial Shuttle, substantially the type which appeared in the original show. The diplomat which arrives carries documents which clearly show the original Cylon Model, once more tying it to the original. Things change, but not radically when the two mechanical Cylons enter and take position on either side of the door. Although their overall design has been updated, the red scanning eye betrays their origins. Then Caprica, a tall beautiful woman in a blood red outfit enters, walks up to the diplomat and asks: “Are you alive?” before planting a passionate Judas kiss on his lips. The camera pulls back to reveal a substantially redesigned Baseship. Form this moment on the stylistic changes come thick and fast when we join the story proper aboard the Galactica. Gone are the blandly bright interiors, to be replaced with a ship which has a much more used military feel. With the ship being turned into a museum, it gives Moore another chance to tie the two shows together via the exhibits.

The new miniseries opens after a forty year truce has been in place. Visually there is little at this stage to differentiate the new series, either in content or stylistically, as the credits open to a shot of a familiar Colonial Shuttle, substantially the type which appeared in the original show. The diplomat which arrives carries documents which clearly show the original Cylon Model, once more tying it to the original. Things change, but not radically when the two mechanical Cylons enter and take position on either side of the door. Although their overall design has been updated, the red scanning eye betrays their origins. Then Caprica, a tall beautiful woman in a blood red outfit enters, walks up to the diplomat and asks: “Are you alive?” before planting a passionate Judas kiss on his lips. The camera pulls back to reveal a substantially redesigned Baseship. Form this moment on the stylistic changes come thick and fast when we join the story proper aboard the Galactica. Gone are the blandly bright interiors, to be replaced with a ship which has a much more used military feel. With the ship being turned into a museum, it gives Moore another chance to tie the two shows together via the exhibits. Here Moore chooses, amongst the familiar or at least vaguely familiar, to introduce one of his most contentious changes, as we follow Starbuck jogging through the interior of the ship. This is not a recognisable Starbuck, as this one is Kara Thrace a woman, played by Katee Sackhoff, who smokes, drinks and fights. Even as a passing fan of the original show I never really understood why this point should have been contentious, nobody complained when Sigourney Weaver played Ripley in Alien (1979), a role that was written for a man. One possible explanation is that as a female character she isn’t, unlike Caprica 6, overtly sexualised. Even in these enlightened times it would seem that we still prefer strong female characters to over emphasis their gender - Angelina Jolie,

Here Moore chooses, amongst the familiar or at least vaguely familiar, to introduce one of his most contentious changes, as we follow Starbuck jogging through the interior of the ship. This is not a recognisable Starbuck, as this one is Kara Thrace a woman, played by Katee Sackhoff, who smokes, drinks and fights. Even as a passing fan of the original show I never really understood why this point should have been contentious, nobody complained when Sigourney Weaver played Ripley in Alien (1979), a role that was written for a man. One possible explanation is that as a female character she isn’t, unlike Caprica 6, overtly sexualised. Even in these enlightened times it would seem that we still prefer strong female characters to over emphasis their gender - Angelina Jolie,  This juxtaposition of the known with the new would be a motif that would reoccur through the whole four seasons - sometimes for continuity, sometime to help the original fans to feel that they might still be in Kansas and sometimes just from a sense of playfulness, witness the Serenity from

This juxtaposition of the known with the new would be a motif that would reoccur through the whole four seasons - sometimes for continuity, sometime to help the original fans to feel that they might still be in Kansas and sometimes just from a sense of playfulness, witness the Serenity from  This need to stamp Moore’s vision on the Galactica universe extended to changing the personality traits of more than one of the cast members. Gone was Lorne Green’s kindly patriarch Adama, to be replaced with Edward James Olmos’s grizzled warrior who had fought in the initial Cylon War. His commitment to his career had cost him a lost marriage, a dead son and the loss of his relationship with his only surviving son. Likewise, Boomer (Grace Park) turned into a woman and Apollo swapped his name for Lee (Jamie Bamber).

This need to stamp Moore’s vision on the Galactica universe extended to changing the personality traits of more than one of the cast members. Gone was Lorne Green’s kindly patriarch Adama, to be replaced with Edward James Olmos’s grizzled warrior who had fought in the initial Cylon War. His commitment to his career had cost him a lost marriage, a dead son and the loss of his relationship with his only surviving son. Likewise, Boomer (Grace Park) turned into a woman and Apollo swapped his name for Lee (Jamie Bamber). But it was a day of reckoning that Moore provided. Examined again, we can see that many of the themes which would be played out across Galactica’s four seasons are already contained in Adama’s speech: themes of religion and philosophy, of existential responsibility and the flawed nature of man. This idea of a flawed creation would see the characters engage in many actions which would be unthinkable on many other shows. President Roslin orders the death of Leoben (Callum Keith Rennie) without considering that she is killing another sentient creature, an act which would otherwise be against her own belief system. This notion of free will, which may initially seem a comfort unfortunately also, involves moral responsibility and the possibility of redemption. It is this which Adama tries to address in his speech - “The day comes when you can't hide from what you've done anymore”. At some time or another all the major characters have to face this moment of truth. Starbuck is the first, quite early on in the story, when she has to admit to Adama that she passed his son, on his flight test, even though he should have failed, an act which contributed to his death. Baltar is put on trial for his actions on New Caprica, Gaeta and Zarek pay the ultimate sacrifice for their betrayal. The most unnerving instance of this is when Saul Tigh literally has to look into the eyes of his wife, whom he had murdered.

But it was a day of reckoning that Moore provided. Examined again, we can see that many of the themes which would be played out across Galactica’s four seasons are already contained in Adama’s speech: themes of religion and philosophy, of existential responsibility and the flawed nature of man. This idea of a flawed creation would see the characters engage in many actions which would be unthinkable on many other shows. President Roslin orders the death of Leoben (Callum Keith Rennie) without considering that she is killing another sentient creature, an act which would otherwise be against her own belief system. This notion of free will, which may initially seem a comfort unfortunately also, involves moral responsibility and the possibility of redemption. It is this which Adama tries to address in his speech - “The day comes when you can't hide from what you've done anymore”. At some time or another all the major characters have to face this moment of truth. Starbuck is the first, quite early on in the story, when she has to admit to Adama that she passed his son, on his flight test, even though he should have failed, an act which contributed to his death. Baltar is put on trial for his actions on New Caprica, Gaeta and Zarek pay the ultimate sacrifice for their betrayal. The most unnerving instance of this is when Saul Tigh literally has to look into the eyes of his wife, whom he had murdered. Adama, who with Roslin, functions in a latter day Moses role, leading their people to the Promised Land, also poses the ultimate question: Why are we here? “Why are we as a people worth saving?” For some in the show the answer was as obvious as it was trite, that their unquestioning belief in a god or gods were enough justification for their existence. And, for the Cylons especially, it was enough for them to unquestionably eradicate the majority of humanity, in the furtherance of their enigmatic plan which was never explained or explored in the four seasons of the show - though it is possibly alluded to in the new show Caprica. Hopefully, when later in the year the Edward James Olmos helmed ‘The Plan’ sees the light of day, some of the questions will be answered.

Adama, who with Roslin, functions in a latter day Moses role, leading their people to the Promised Land, also poses the ultimate question: Why are we here? “Why are we as a people worth saving?” For some in the show the answer was as obvious as it was trite, that their unquestioning belief in a god or gods were enough justification for their existence. And, for the Cylons especially, it was enough for them to unquestionably eradicate the majority of humanity, in the furtherance of their enigmatic plan which was never explained or explored in the four seasons of the show - though it is possibly alluded to in the new show Caprica. Hopefully, when later in the year the Edward James Olmos helmed ‘The Plan’ sees the light of day, some of the questions will be answered.

Fears about the consequences of creating life in mans image or otherwise has been a rich part of our fiction. The earliest serials like Homunculus (1915) where a scientist creates life which is evil, that is finally destroyed with a bolt of lightning, possibly from God. Metropolis (1927) went a step further with the robotic Maria who becomes indistinguishable to the original, except for her heightened sexuality, a little like Caprica 6. Once more mankind is nearly brought to its knees by its own creation and of course poor Victor Frankenstein is destroyed by his own creation. The book’s subtitle “The Modern Prometheus” acted as a warning to mankind that there are some things which should not be attempted, the creation of life is one of them. The sentient races in Galactica have yet to learn the lesson of Prometheus who was condemned to repeat the same torture over and over again for stealing fire - the essence of life - from the gods. The punishment holds not just for biological human life but also for artificial life. Like the computer in Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970) and the Robots in

Fears about the consequences of creating life in mans image or otherwise has been a rich part of our fiction. The earliest serials like Homunculus (1915) where a scientist creates life which is evil, that is finally destroyed with a bolt of lightning, possibly from God. Metropolis (1927) went a step further with the robotic Maria who becomes indistinguishable to the original, except for her heightened sexuality, a little like Caprica 6. Once more mankind is nearly brought to its knees by its own creation and of course poor Victor Frankenstein is destroyed by his own creation. The book’s subtitle “The Modern Prometheus” acted as a warning to mankind that there are some things which should not be attempted, the creation of life is one of them. The sentient races in Galactica have yet to learn the lesson of Prometheus who was condemned to repeat the same torture over and over again for stealing fire - the essence of life - from the gods. The punishment holds not just for biological human life but also for artificial life. Like the computer in Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970) and the Robots in  Where Galactica diverges from many of the shows, when it includes religious elements, which preceded it is in its equal acceptance of the validity of both the monotheistic faith of the Cylons and the polytheistic pantheon of gods that the colonists worship. This is not the first time this has happened, even the Imaginary ‘Force’ is treated reverentially in Star Wars (1977). This allocation of faith systems sets up an uncomfortable resonance in the audience. Many, if not most, will adhere to the monotheistic view of a single god, but Galactica ascribes these religious attributes to what is initially viewed as the bad guys. So, if we are cheering on the race that more closely adheres to a lot of peoples religious sensibilities, are we making a pact with the devil? Galactica makes no such distinction. The belief in a pantheon of gods, based loosely on Greek mythology, is given both equal time and importance. it's use is reminiscent of many human conflicts where both parties believe that God is on their side.

Where Galactica diverges from many of the shows, when it includes religious elements, which preceded it is in its equal acceptance of the validity of both the monotheistic faith of the Cylons and the polytheistic pantheon of gods that the colonists worship. This is not the first time this has happened, even the Imaginary ‘Force’ is treated reverentially in Star Wars (1977). This allocation of faith systems sets up an uncomfortable resonance in the audience. Many, if not most, will adhere to the monotheistic view of a single god, but Galactica ascribes these religious attributes to what is initially viewed as the bad guys. So, if we are cheering on the race that more closely adheres to a lot of peoples religious sensibilities, are we making a pact with the devil? Galactica makes no such distinction. The belief in a pantheon of gods, based loosely on Greek mythology, is given both equal time and importance. it's use is reminiscent of many human conflicts where both parties believe that God is on their side. This is a deliberate theological point which the show makes. Towards the close of the last season we, as an audience, are informed, by head Baltar and head 6, that not only does God exist, but that firstly he doesn’t really like being referred to as such and, secondly, he is certainly not on anybody’s side. This opens up the possibility that both the humans and Cylons could be equally right or wrong in their notion of God. If this were the case how, as an audience, are we to make sense of the numerous visions which pepper the show, including the portentous visions of the future which are given to Baltar, Roslin, Caprica 6 and Kara? It would seem that the visions of the opera house do come true, as do Kara’s paintings of the damaged Baseship. The show even implies that Kara has been groomed, so to speak, from an early age, so that she is in the correct position to jump the Galactica to safety. The lack of answers and the multilayered manner in which religion is introduced often leaves many questions unanswered. Roles appear interchangeable over the course of the show with more than one character taking on the messianic role.

This is a deliberate theological point which the show makes. Towards the close of the last season we, as an audience, are informed, by head Baltar and head 6, that not only does God exist, but that firstly he doesn’t really like being referred to as such and, secondly, he is certainly not on anybody’s side. This opens up the possibility that both the humans and Cylons could be equally right or wrong in their notion of God. If this were the case how, as an audience, are we to make sense of the numerous visions which pepper the show, including the portentous visions of the future which are given to Baltar, Roslin, Caprica 6 and Kara? It would seem that the visions of the opera house do come true, as do Kara’s paintings of the damaged Baseship. The show even implies that Kara has been groomed, so to speak, from an early age, so that she is in the correct position to jump the Galactica to safety. The lack of answers and the multilayered manner in which religion is introduced often leaves many questions unanswered. Roles appear interchangeable over the course of the show with more than one character taking on the messianic role. Messianic characters are not unknown in science fiction, both written and filmed. Valentine Michael Smith, (Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein pub. 1961) - Klattu (

Messianic characters are not unknown in science fiction, both written and filmed. Valentine Michael Smith, (Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert Heinlein pub. 1961) - Klattu ( Galactica’s vision of God also nicely bypasses the deterministic problem of free will Vs an omnipotent creator. This God leads and nudges his creations to get a desired outcome - “All this has happened before, all of this will happen again” - an omnipotent God would not need to go through so many iterations of creation, therefore his creations really do have free will. This is actually a simplistic view of the concept of God in Galactica. If God was tinkering, trying to get it right, how do we then explain Roslin’s visions which ultimately come true? Or that Leoben is able with some accuracy to predict Kara’s finding of Kobol and Earth? If the characters had true free will none of this would be known.

Galactica’s vision of God also nicely bypasses the deterministic problem of free will Vs an omnipotent creator. This God leads and nudges his creations to get a desired outcome - “All this has happened before, all of this will happen again” - an omnipotent God would not need to go through so many iterations of creation, therefore his creations really do have free will. This is actually a simplistic view of the concept of God in Galactica. If God was tinkering, trying to get it right, how do we then explain Roslin’s visions which ultimately come true? Or that Leoben is able with some accuracy to predict Kara’s finding of Kobol and Earth? If the characters had true free will none of this would be known.